Between Saturdays: The Gut Glow-Up Secret That Works Faster Than Fiber Alone

Why fermented foods quietly dial down inflammation and boost microbiome magic in weeks while fiber plays the long game and how to sequence them for effortless radiance from the inside out.

“Eat more fiber” has become one of nutrition’s most repeated instructions. Fermented foods are often mentioned in the same breath. Both feed the gut, but they don’t behave the same way and they don’t act on the same timeline. This week’s studies show that what we feed the microbiome matters less than how ready it is to respond.

Caught My Eye…

• Fermented Foods and Inflammation

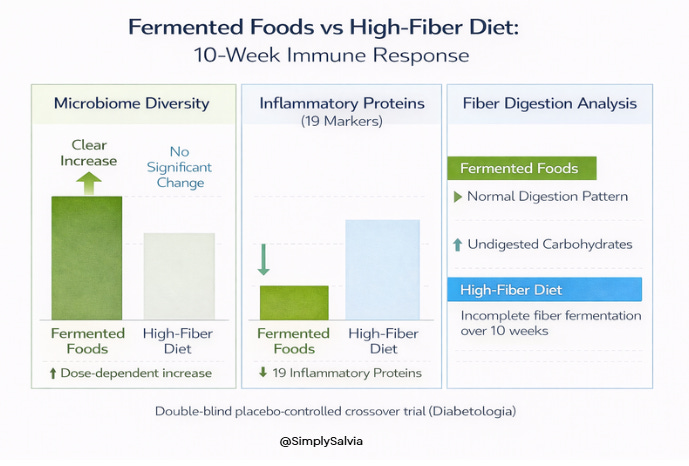

In a 10-week randomized trial published in Cell, 36 healthy adults were assigned to either a fermented-food diet or a high-fiber diet. The results surprised many.

Participants eating fermented foods showed a clear increase in gut microbiome diversity, and the more fermented food they ate, the stronger the effect. At the same time, markers of immune activation fell across four immune cell types. Blood tests showed reductions in 19 inflammatory proteins, including IL-6, a key signal linked to chronic inflammation.

The high-fiber group did not show the same short-term immune shift. None of the 19 inflammatory proteins decreased, and microbiome diversity stayed roughly stable on average.

Stool analysis offered a clue: more undigested carbohydrates appeared in the fiber group’s stool, suggesting that fiber breakdown was incomplete over this time frame. The authors noted that many people in industrialized societies may lack sufficient fiber-degrading microbes for rapid response.

In other words, fermented foods appeared to bring microbes with them, while fiber depended on microbes that weren’t always there yet.

• Fiber Interventions

A large systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 randomized controlled trials examined how fiber interventions affect the microbiome in healthy adults.

Fiber supplementation reliably increased specific beneficial bacteria. Bifidobacterium rose substantially, and Lactobacillus increased modestly, particularly with fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS). These changes were consistent across studies.

However, overall microbiome diversity did not significantly change. Fiber shifted who was present, not how diverse the ecosystem became. Fecal butyrate — a key short-chain fatty acid increased slightly, but the effect was small.

The pattern suggests that fiber acts like selective fertilizer. It feeds certain microbes very well, but it doesn’t rapidly rebuild the ecosystem as a whole.

• Fiber, SCFAs, and expectations vs reality

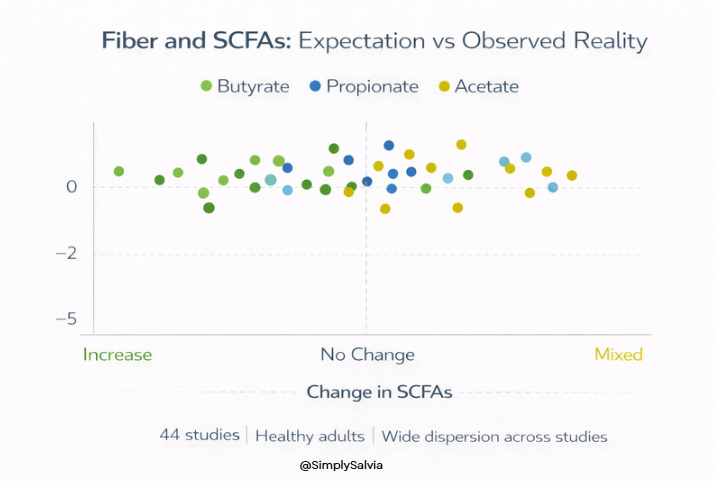

A separate systematic review in Nutrients looked more closely at fiber’s effects on short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are often cited as fiber’s main metabolic benefit.

Across 44 studies, results were mixed. Some showed increases in total SCFAs, others showed no change. Individual SCFAs often remained unchanged. Outcomes depended heavily on fiber type, structure, and dose, as well as how SCFAs were measured.

The authors concluded that while fiber can alter microbiota and metabolites, there is no single, consistent SCFA response in healthy adults. Fiber works but not uniformly, and not instantly.

• Diet Can Reshape the Microbiome Within Days

A landmark Nature study showed just how fast diet can act. Ten adults completed two short diet phases: one animal-based, one plant-based, with daily stool sampling.

Microbial community structure shifted within a single day of dietary change, temporarily overpowering individual differences. The animal-based diet increased bile-tolerant microbes such as Bilophila, while reducing plant-fiber specialists. Fecal bile acids trended upward on the animal-based diet, a pathway mechanistically linked to inflammatory bowel disease risk though no disease outcomes were measured.

Despite these rapid shifts, overall microbiome diversity did not significantly change during either short phase.

The takeaway: composition changes quickly; ecosystem rebuilding does not.

These studies point to a quiet but important distinction.

Fermented foods act like microbial delivery systems, introducing organisms that can interact with the immune system almost immediately. Fiber works differently. It asks the microbiome to grow new capacity — a slower, more conditional process.

Neither is superior. They operate on different clocks.

In bodies shaped by modern diets, convenience has reduced not only fiber intake, but microbial readiness. When fiber arrives without the microbes needed to use it, benefits may lag. Fermented foods, by contrast, bypass that bottleneck at least temporarily.

Health, here, looks less like choosing sides and more like sequencing: first restore, then feed.

Detailed Readings

Dietary fiber interventions meta-analysis

Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome