Between Saturdays: The Hidden Reason Modern Food Makes You Hungrier (Even When It’s “Healthy”)

How ultra-processing quietly hijacks your body’s natural “I’m full” signals and the simple texture + pace shifts that restore effortless balance, glow, and energy.

Modern food isn’t just different in ingredients. It’s different in structure. Grinding, refining, emulsifying, extruding, and flavor-enhancing don’t merely change taste or shelf life, they change how the body interprets a meal. Calories arrive faster, textures dissolve sooner, and signals meant to guide hunger, fullness, and energy balance blur. This week’s studies explore what happens when food becomes easier to eat than the body evolved to process.

Caught My Eye…

Ultra-Processed Foods and Excess Energy Intake

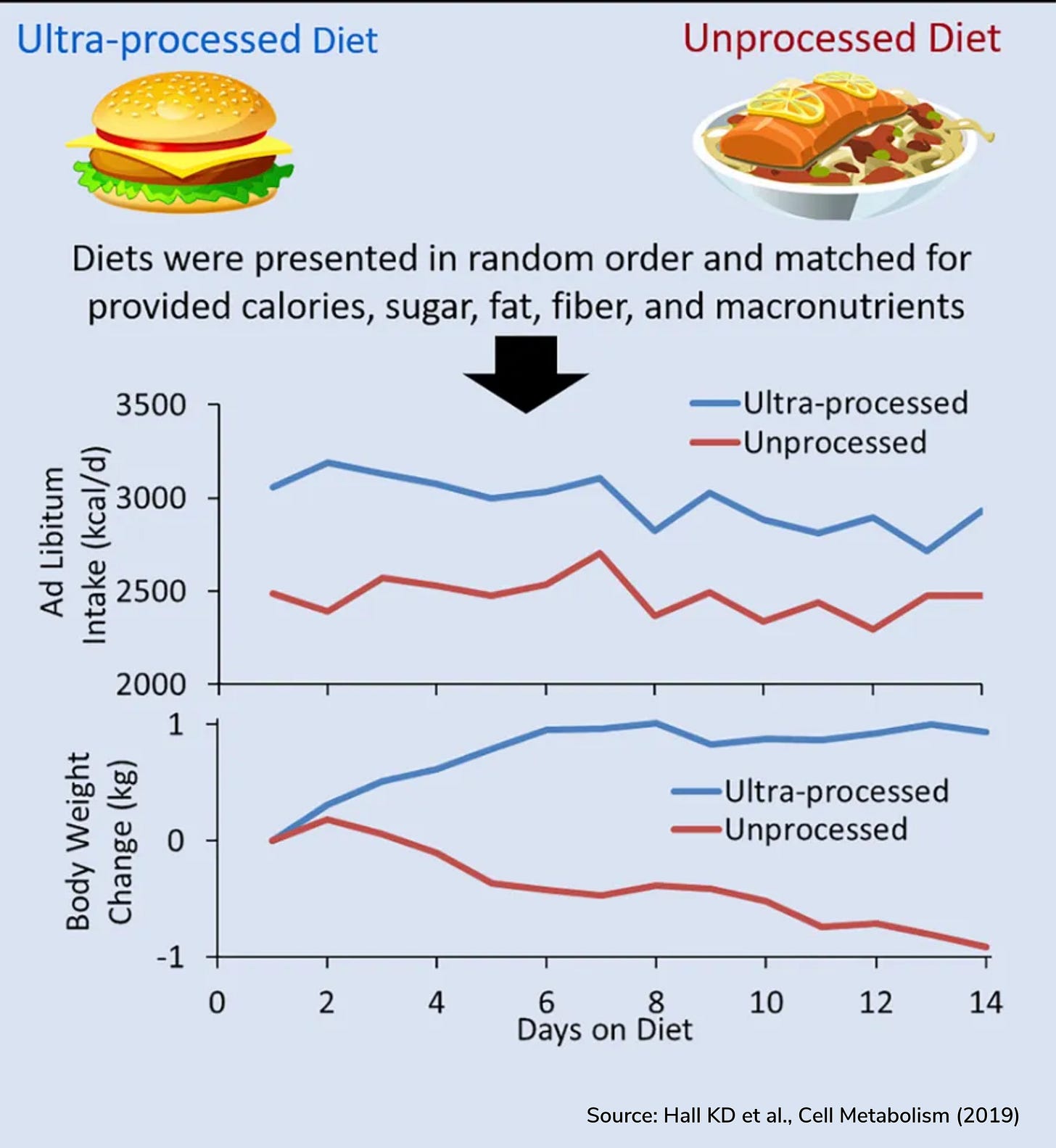

In a tightly controlled inpatient crossover trial published in Cell Metabolism, researchers fed adults two diets for two weeks each: one composed mostly of ultra-processed foods, the other of minimally processed foods. Importantly, the diets were matched for calories, fat, carbohydrate, sugar, fiber, and sodium.Despite this, participants ate an average of about 500 extra calories per day on the ultra-processed diet. They also gained weight, while they lost weight on the minimally processed diet.

The difference wasn’t taste or enjoyment. It was speed. Ultra-processed foods were eaten faster, and fullness arrived later. Satiety signals simply didn’t have time to catch up before calories were already consumed.

The study made one thing very clear: processing itself can override the body’s natural appetite controls, even when nutrients look identical on paper.

Food Texture, Eating Rate, and Satiety Hormones

Why does eating speed matter so much? Two experimental studies help explain.In a controlled feeding trial published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, researchers found that fewer chews per bite led to lower release of satiety hormones, including GLP-1 and PYY. Participants consumed more food before feeling full, simply because the hormonal feedback loop was delayed.

A second study in Appetite showed that softer, more processed foods are eaten more rapidly than foods requiring chewing and structural breakdown. Faster eating translated into higher energy intake, independent of hunger or preference.

Together, these studies show that texture is not cosmetic. Chewing time is part of how the body measures a meal. When processing removes resistance, fullness arrives late and excess intake becomes almost automatic.

Processing, the Gut–Brain Axis, and Inflammation

Beyond eating speed, ultra-processed foods also reshape the gut environment, which plays a central role in appetite and metabolic regulation.Animal studies published in Nature demonstrated that dietary emulsifiers, additives common in ultra-processed foods altered gut microbiota, increased intestinal permeability, and triggered low-grade inflammation linked to metabolic syndrome.

Human-focused reviews reinforce the same pattern. Diets dominated by ultra-processed foods are associated with disrupted gut–brain signaling, insulin resistance, and impaired appetite control. Chronic inflammation interferes with how the brain interprets energy status, leaving hunger signals noisy and unreliable.

Processing doesn’t just change digestion it changes communication between the gut and the brain.

Metabolic Risk Beyond Calories

Large prospective cohort studies consistently show that higher ultra-processed food intake is linked to higher risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and all-cause mortality.

What’s striking is that these associations persist even after adjusting for total calories, sugar, fat, fiber, and BMI. In other words, people aren’t getting sick simply because they eat more, they’re getting sick because processing changes how metabolism behaves over time.

Ultra-processed foods appear to create a state of metabolic confusion: frequent glucose spikes, impaired satiety, altered lipid handling, and chronic inflammatory signaling all without necessarily increasing visible overeating.

Ultra-processed foods succeed because they solve real problems: speed, affordability, accessibility. But biology doesn’t adapt at the same pace as industry. When meals require little chewing, digest instantly, and deliver calories faster than hormonal feedback can respond, the body is left managing consequences rather than making choices.

This isn’t about purity or perfection. It’s about recognizing that food structure carries information. The more processing strips away time, texture, and resistance, the less guidance the body receives. Over years, that mismatch accumulates quietly reshaping appetite, weight, and metabolic health.

Detailed Readings

Ultra processed diets causes excess calorie intake and weight gain

Oral processing characteristics of solid foods relate to eating rate and energy intake, appetite.

Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome

The Western Diet-Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease