Between Saturdays: How to Help Your Body Unwind (What Actually Works)

Breathwork lowers self-reported stress reliably. Mindfulness softens anxiety & depression. Progressive relaxation eases high-stress bodies. Green environments reduce cortisol.

Stress reduction advice is everywhere, but not all strategies act on the body in the same way. Some work through breathing and the nervous system, others through attention, movement, or environment. This week’s studies look at four commonly recommended approaches and ask a practical question: do they measurably reduce stress and if so, how reliably?

Caught My Eye…

Breathwork

A meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials (785 participants) examined paced or slow breathing practices, often modeled after pranayama-style techniques. Across studies, breathwork was associated with a small to moderate reduction in self-reported stress compared with control conditions.

The effect size wasn’t large, and some trials had methodological limitations, but the signal was consistent. Slow breathing appears to work by directly engaging the parasympathetic nervous system, lowering heart rate and dampening stress-related arousal.

Breathwork isn’t a cure, but it may be one of the most direct ways to interrupt stress physiology in real time especially during moments of acute overload.

Mindfulness meditation

A large systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 trials involving more than 3,500 participants evaluated structured mindfulness meditation programs. The authors found small to moderate improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms, with more modest and less consistent effects on stress and distress specifically.

This distinction matters. Mindfulness may not eliminate stressors, but it appears to change how stress is perceived and processed, reducing downstream emotional reactivity. Evidence quality varied, and benefits depended on program structure and participant engagement.

Mindfulness works less like a switch and more like a lens, subtle shifts that accumulate over time.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

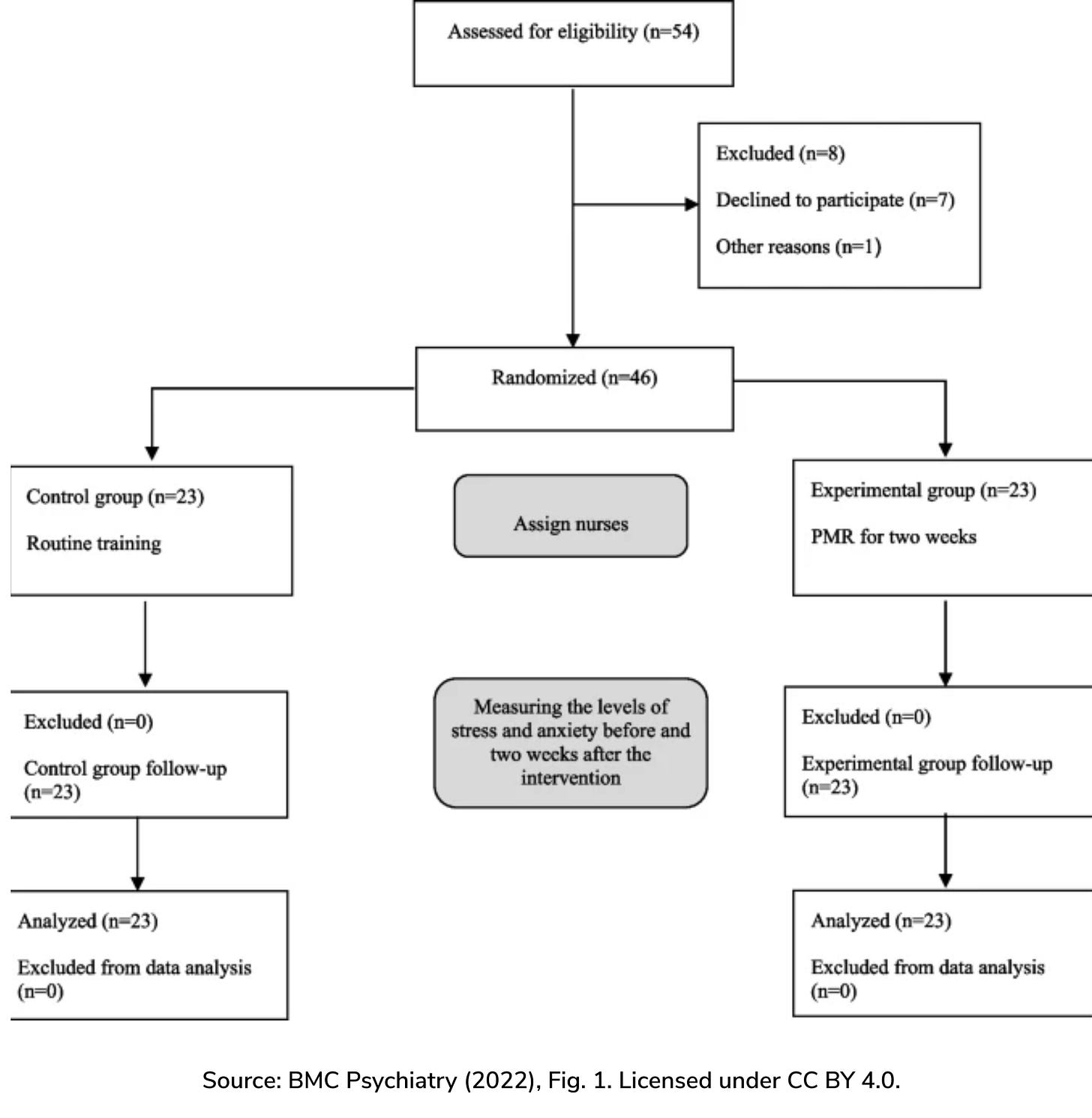

In a randomized clinical trial among nurses, a population with high occupational stress. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) training led to significant reductions in both stress and anxiety compared with a control group.

Stress levels fell in the intervention group while remaining higher in controls, with strong statistical significance after the training period. PMR works by systematically contracting and releasing muscle groups, helping the nervous system recognize the difference between tension and rest.

The evidence here is more population-specific, but it highlights something often overlooked: stress is stored physically, and relaxing the body can quiet the mind.

Forest bathing

A systematic review and meta-analysis examined studies comparing time spent in forest or green environments with urban settings. Across trials, participants showed lower salivary cortisol levels, a biological marker of stress after forest exposure.

The pooled effects were statistically significant, though the authors noted variability in study design and exposure duration. Still, the direction was consistent: natural environments appear to downshift stress physiology, even without structured interventions.

Sometimes stress reduction isn’t something we do it’s something the environment allows.

These approaches share a common thread: they don’t remove stressors; they change how the body responds. Breath slows the nervous system. Mindfulness reshapes attention. Muscle relaxation releases stored tension. Nature lowers baseline arousal.

None of these are silver bullets. The effects are modest, and evidence quality varies. But stress biology is cumulative and so are small interventions. Over time, repeated signals of safety matter.

Next week, we’ll explore which stress-recovery strategies have the strongest physiological effects over the long term, and where lifestyle changes outperform techniques.

Detailed Readings

Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials

Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being

Effects of forest bathing (shinrin-yoku) on levels of cortisol as a stress biomarke