Between Saturdays: Why Your Body Feels Stress Long Before Your Mind Does

Emerging research on how chronic pressure moves silently through heart, immune system, sleep, and mood.

Stress is often treated as a feeling, something abstract or psychological. But biologically, stress is a signal, one that travels through hormones, nerves, immune cells, and circadian rhythms. When that signal is brief, the body adapts. When it’s constant, systems begin to shift. This week’s studies trace how chronic stress shows up in measurable ways across physical and mental health.

Caught My Eye…

Cardiovascular risk

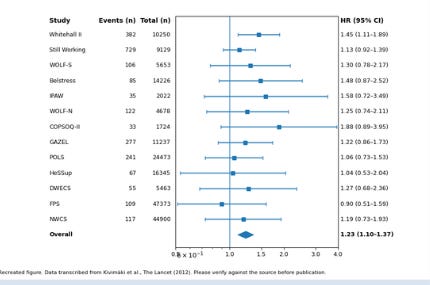

A large individual participant meta-analysis pooled data from 197,473 adults to examine whether job strain, high demands paired with low control can predicts heart disease. Over follow-up, people exposed to job strain had a 23% higher risk of developing coronary heart disease compared with those without strain.

This wasn’t explained away by smoking, socioeconomic status, or baseline health. The association held after adjustment, suggesting stress itself contributes to cardiovascular risk likely through repeated activation of stress hormones, elevated blood pressure, and inflammatory pathways.

The takeaway is simple but sobering: chronic work stress doesn’t just feel hard it leaves a cardiovascular footprint.

Stress and immune function

A sweeping meta-analysis of 300+ studies examined how stress affects the immune system. The pattern was striking.

Acute stress aka short-lived challenges temporarily boosted certain immune responses. This makes evolutionary sense: the body prepares for injury or infection.

Chronic stress, however, showed the opposite effect. Over time, it was linked to suppressed cellular and humoral immunity, reduced immune surveillance, and impaired antibody responses.In other words, stress flips from adaptive to harmful when it becomes constant. The immune system shifts from readiness to exhaustion, leaving the body less able to respond to threats.

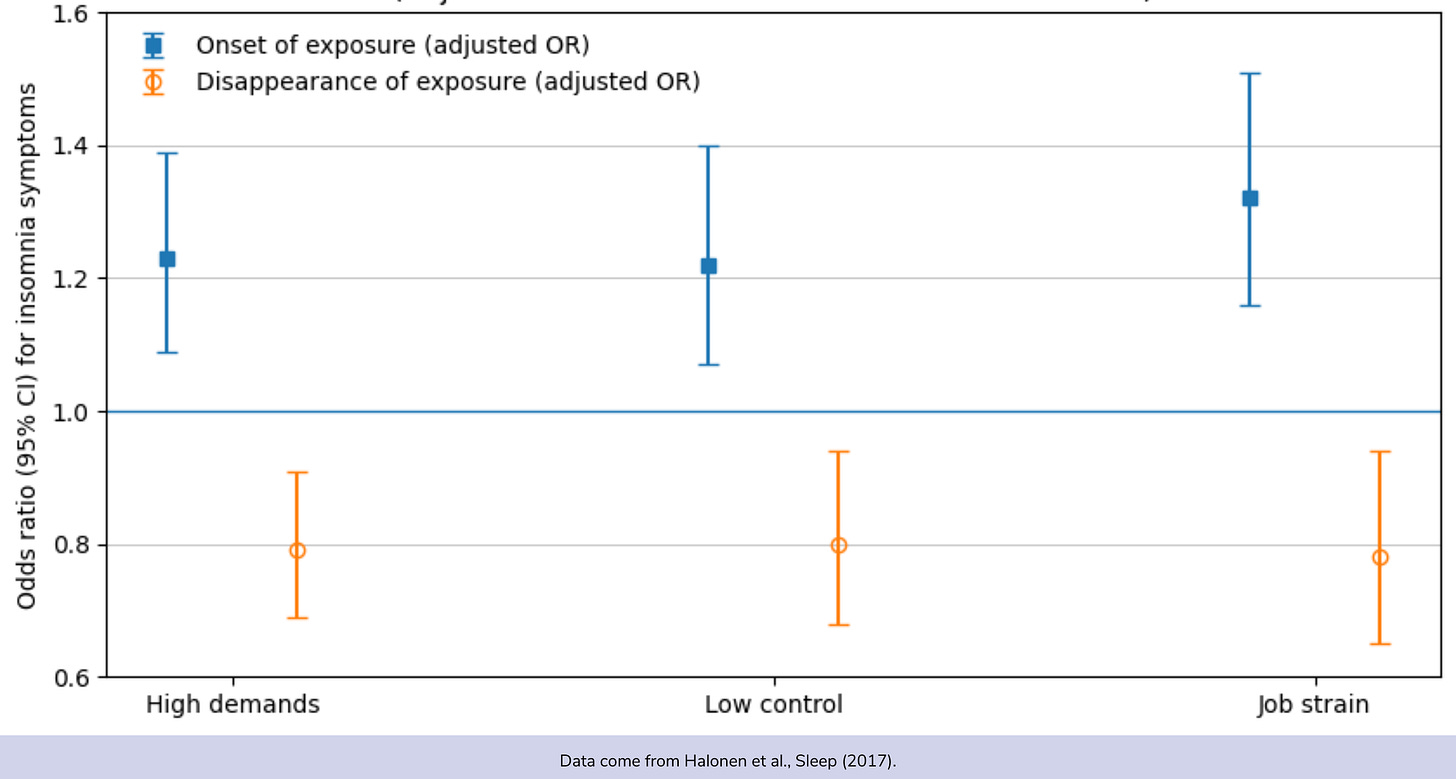

Job strain and sleep

In a large observational “pseudo-trial,” researchers tracked changes in job strain and sleep over time. When job strain appeared, the odds of developing new insomnia symptoms rose by about 32%. When job strain resolved, the odds of repeated insomnia symptoms dropped.

This matters because it suggests directionality. Stress wasn’t just correlated with poor sleep. Changes in stress preceded changes in sleep. And importantly, improvement in stress was followed by improvement in sleep.

Sleep disruption, here, wasn’t permanent damage. It was a physiological response to ongoing pressure.

Stress and depression

A longitudinal study of university students followed perceived stress and depressive symptoms across time. The relationship ran both ways. Higher stress predicted later depressive symptoms, and higher depressive symptoms predicted later stress.

This bidirectional pattern helps explain why stress and depression are so hard to untangle clinically. Stress increases vulnerability to low mood, and low mood makes everyday demands feel more stressful thus reinforcing the cycle.

While not a randomized trial, the repeated-measures design strengthens confidence that this is more than coincidence. Stress and mental health continually shape each other, especially in early adulthood.

Across these studies, stress emerges not as a single exposure but as a system-wide influence. It tightens blood vessels, quiets immune defenses, fragments sleep, and feeds into mood, often simultaneously.

What’s striking is that stress relief showed benefits too. When job strain eased, sleep improved. When pressure lifted, physiological systems began to recalibrate. This suggests that stress-related damage isn’t always fixed. It’s often responsive to context.

Health isn’t only about what we eat or how we move. It’s also about the environments we endure and the signals they send, day after day.

Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry

The Longitudinal Relationship Between the Symptoms of Depression and Perceived Stress